Summer playin', had me a blast.

I don’t know if I’ve ever played a video game quite like Natsu-Mon: 20th Century Summer Kid. Imagine a JPRG where the young hero who’s supposed to embark on an epic adventure to save the kingdom doesn’t actually embark, and instead just spends a month fishing, exploring caves, and resurrecting the town festival. That’s this game.

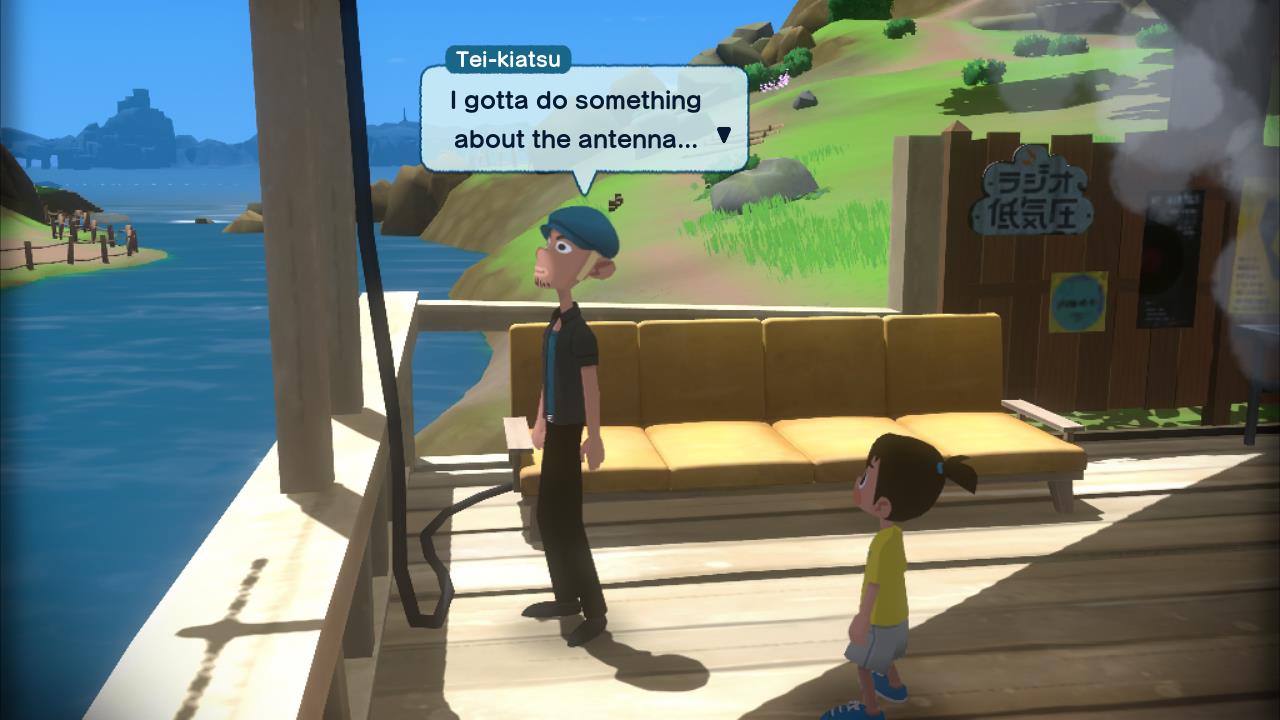

But that’s not to say there’s no adventure to be had. On the contrary, Natsu-Mon is all about finding your adventures where you are. You play as Satoru, a young boy whose parents run a traveling circus. The circus runs into some issues in scenic Yomogi Town, so Satoru is left in the care of an innkeeper while his parents attempt to resolve those issues. With nothing more than his childhood curiosity and a school assignment to guide him, Satoru sets out to make this an August to remember.

And how does he do that? By exploring. By talking to people. By basically just running around until something catches his eye. Gameplay is mostly centered around total childhood freedom—the kind few kids have anymore, at least where I live.

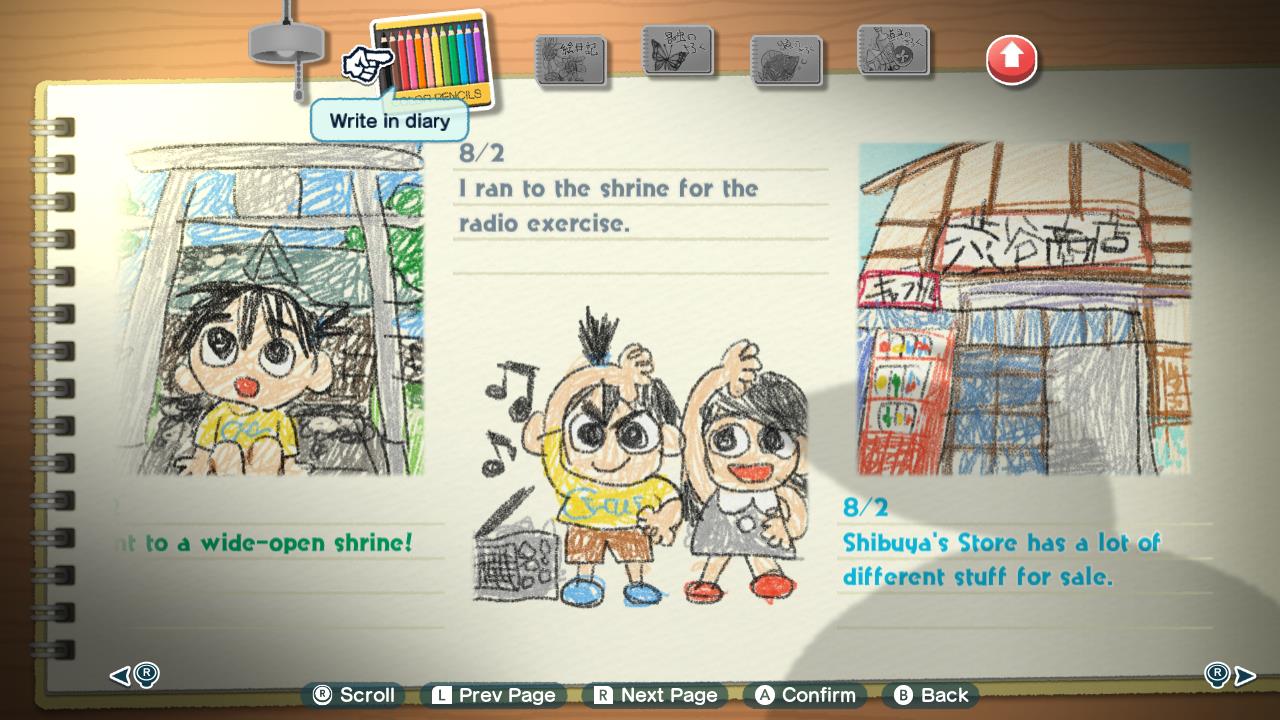

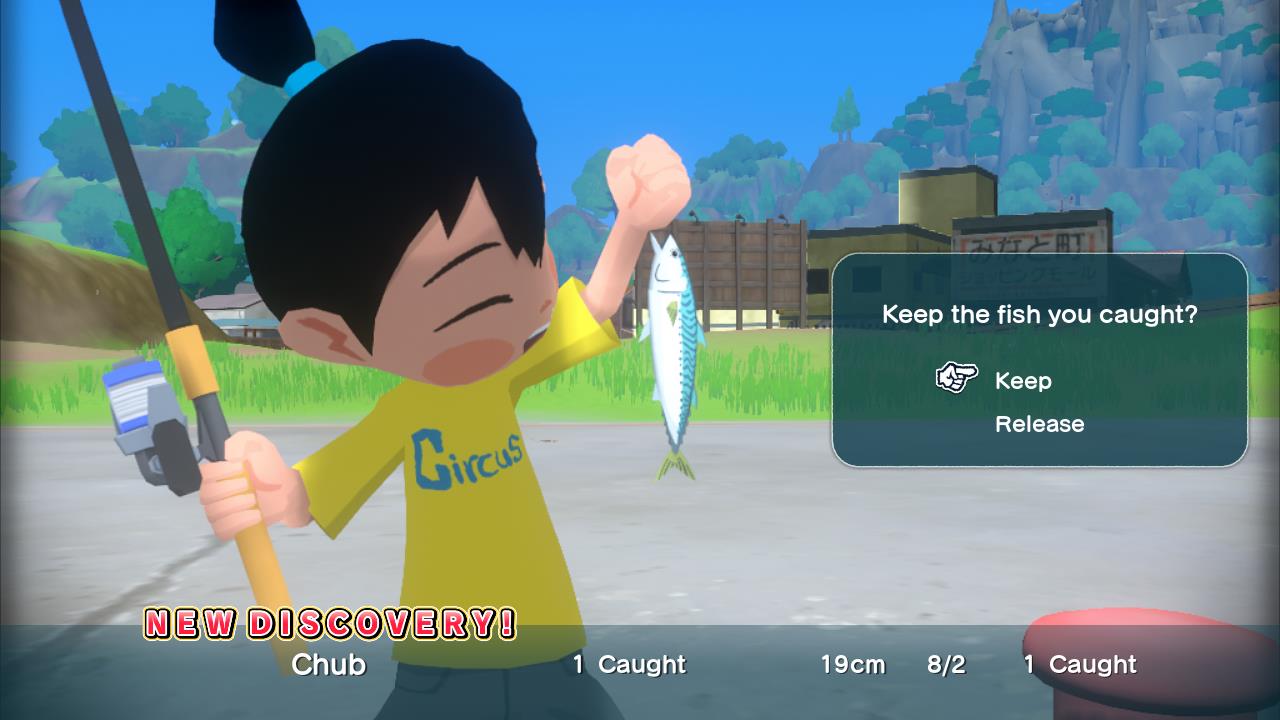

Occasionally, the game gives Satoru specific tasks to complete. He may wake up, for example, and find himself invited to accompany friends to a specific location. These provide scripted moments that help prevent Natsu-Mon from feeling completely aimless. For the most part, however, how Satoru spends his day is up to the player. There are always bugs and fish to catch, all of which are documented in his notebook.

There are coins and treasures to find (were 20th-century Japanese homeowners really this cool with kids traipsing across their rooftops?). There are paid jobs to accept. There are ghost girls to…wait. Ghost girls?

Part of what makes Natsu-Mon: 20th Century Summer Kid so endearing is that it expertly captures the wonder of being a kid. Did that little girl by the tree just vanish into thin air? Is she a ghost? Well, unless someone has a better explanation, she has to be. Let’s play games with her and find out!

Natsu-Mon provides bigger goals, too. One of your first tasks is to climb some specific buildings. Your stamina meter, however, won’t let you get close. So, you have a month to increase the meter and figure out how to get to the top of those structures. What a great goal that is. I recall my own childhood when a friend and I decided to hop the barbed-wire security of a radio tower and climb to the top. Did we make it? Of course not. Our stamina meters weren’t high enough. And it was also quite scary. And stupid. But we tried. Memory achieved!

Satoru has to uncover and complete all of these tasks over the course of a full day. They begin with breakfast and a morning exercise session (provided he was home in time for a good night’s sleep the day before).

Then, he’s free to roam until supper when he’s automatically located and returned home. He then gets the evening to wrap things up, but has to be home by 10:00 if he doesn’t want to oversleep the next day. This was annoying at first, as the game didn’t provide a clock; you have to buy that yourself once you make enough money. Maybe the point was to miss your bedtime, but I preferred to just hang around the inn until weariness took over. Even with the clock, it sometimes wasn’t worth abandoning my current task to complete the long journey home in time for bed, even with the ability to take the bus.

The length of the days can be adjusted to suit your playstyle. You can get more done by making the days last longer, but the adventures lose their sense of urgency. You also lose replayability that way. Tear through the game on short days, and you’ll be more likely to play again, making different decisions on how you spend your time. Shorter days, however, also make it more difficult to complete certain assignments and jobs, which can be frustrating (especially those that require precise movements).

This is especially true of the tasks that require platforming or reaching far-off locations. The game’s open world is colorful and nicely detailed, but getting around can sometimes prove difficult. This is largely due to somewhat clunky controls, especially when platforming is in the mix. And because Satoru can climb nearly anything, he’ll often start climbing things you don’t want him to.

Natsu-Mon also doesn’t do a great job of guiding you on your tasks, or even helping you figure out how to go to bed. Random exploration was very fun at the beginning, but by the time you’re approaching the end of August, a little more help on how to get things done would’ve been appreciated. A fortune-telling circus member eventually shows up to help, and you may even locate a mystical port-a-pot to help you get home in an instant. Still, expect some gaming sessions to be more productive than others. Maybe that’s a development decision—you can’t expect to complete a childhood’s worth of adventures in a month, right? Especially when there’s already a DLC adventure to embark on.

Also, it forces you to talk to people, and that’s one of the game’s greatest strengths. Almost every person you meet has something to contribute. Even better, their individual quirks (and Satoru’s response to them) make them fun to engage with. The conversations are a joy to experience, even if you are oddly forced to select every dialogue option before leaving them. And, like in real life, you never know which conversation will end up shaping the course of your summer.

These all combine to create a chill, Animal Crossing-type experience that will make older gamers wistful. It affected me a bit differently, as I had these types of days in my childhood. I explored creek bridges in search of black snakes. I climbed abandoned grain silos. I never hopped on a box car and rode it 30 miles into a neighboring town before disembarking and calling my dad for a ride home, but I have a buddy who did.

Rather, Natsu-Mon makes me wistful for an environment where kids still have this type of freedom (or even just desire it). I imagine that’s why the game was made, as that sense of wonder and curiosity is deeply woven into its core. That makes it a game worth experiencing, provided childhood adventures haven’t lost their appeal. Who needs to go fight God on some interstellar plane when there’s a lighthouse to climb literally right there?

Review: Natsu-Mon: 20th Century Summer Kid (Nintendo Switch)

Great

Natsu-Mon: 20th Century Summer Kid provides a gaming adventure as cozy as its name. Its stakes may be low, but it packs in plenty to accomplish and will have players feeling nostalgic for a time they may have never even experienced.