Domo arigato, Mr. Roboto.

When you first launch Horace, you’re greeted with a play on the Thames Television ident. Being American, I know this solely from watching The Benny Hill Show on UHF back in the late ’70s and early ’80s. I point this out not to show my age, but to make it clear that Horace makes a lot of reference jokes, and it has no concern for whether modern gamers are going to get them.

Horace is a puzzle platformer about a robot trying to discover his purpose in life. I can’t offer more details without providing spoilers, but I can say he was created by a kindly old man hired to build robots for use in war. In fact, the “training” levels involve Horace showing off his new abilities to the government types who apparently are behind the project.

But along the way, Horace takes to the family with which he lives. There are moments both touching and funny as he comes to know the people of the house and they come to terms with him. And, being a newly created robot, Horace is naive about the reasoning of humans. His analytical deductions of the actions we make by gut or heart are simultaneously endearing and disheartening, but always hopeful.

And quite often funny. The entire story is told from Horace’s point-of-view, and the developers use this to offer detached pop-culture references and jokes. These usually come in the form of movies and TV shows, such as Star Wars and Coronation Street. I only know of the latter because of Queen’s video for “I Want to Break Free,” but that’s kind of the point. I’m sure there’s a lot of comedy I completely missed, but that’s okay; Horace’s delivery is so dead-pan that you don’t always know when a joke has been made. You rarely feel like you’re missing something.

It helps that the story and gameplay are very good at pushing things along. The initial levels establish Horace’s relationship with the various characters. While trying to find his purpose, he uses his platforming abilities to get a few of them out of dangerous situations. He eventually determines that his mission in life is to “clean one million things.” Impossible? Maybe, until we leave the lengthy introduction and the story zings us with a reason as to why there’d be one million things to clean up.

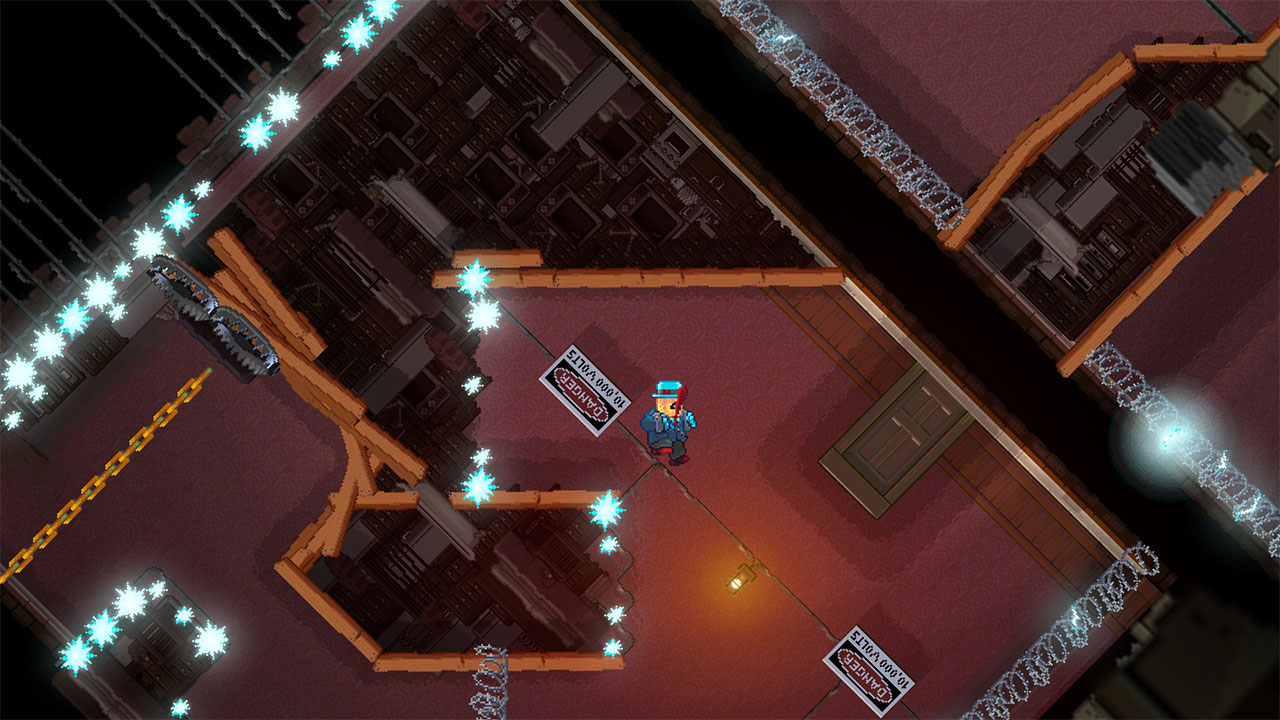

Up until this point, the game struck a skillful balance between gameplay and story-telling. The gameplay takes over in act 2, however, and becomes quite demanding. He’s forced out into the world, and the world is filled with electrified walls, flying chainsaws, water (Horace is electronic, remember), and a lot of evil robots and bosses. For the most part, Horace’s only method to overcome these obstacles is to find a way around them, so he must use his abilities and intelligence to get past. That includes speed, jumping, strength, and the ability to walk on walls and ceilings. The latter is not just useful, it’s fun. The entire room will scroll around as he leaves the floor (Horace always stays centered on the screen).

The effect is kind of trippy, but you get used to it quickly. You have no choice.

Most of the platforming is centered on puzzle solving. How can Horace use the environment to get from point A to point B without get electrocuted or smashed, for example? But there are certain moments were well-timed and precise jumps will be necessary, and there are also a lot of speed runs.

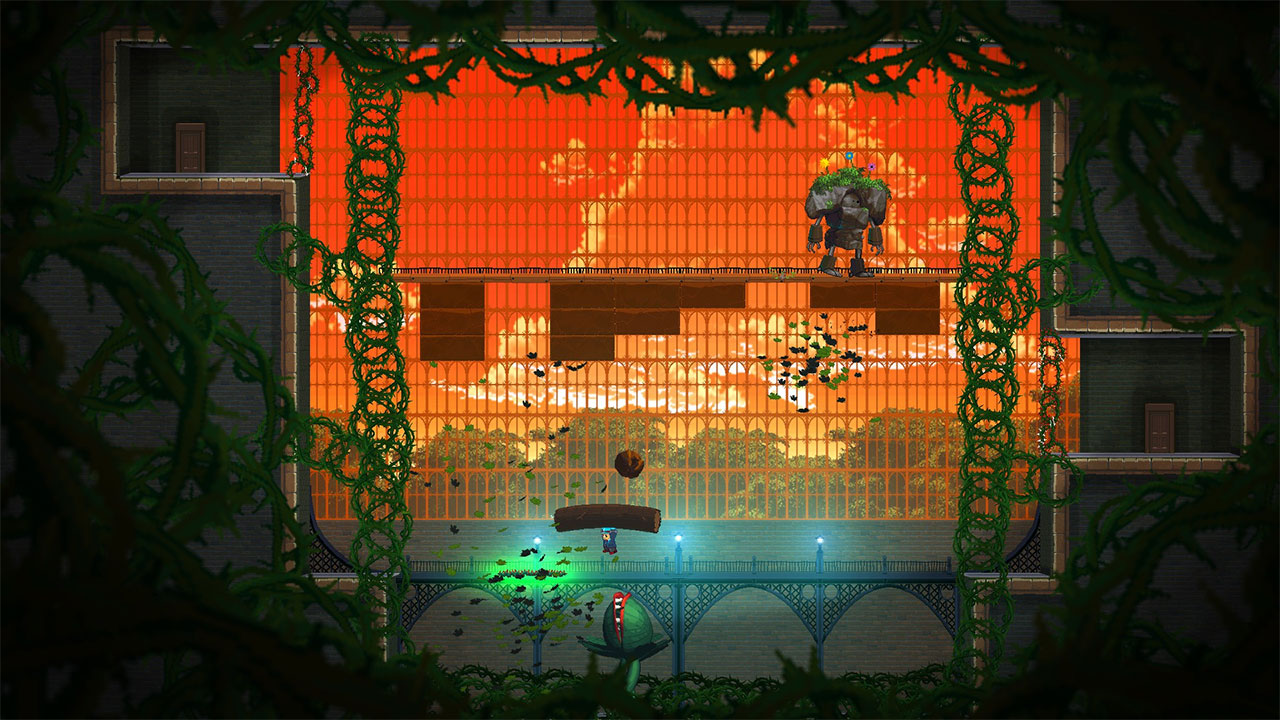

Now and again, you’ll also meet some pretty tricky bosses. You’ll need to figure out how to eliminate them, then put your plan into effect. These bosses are a lot of fun (the giant army tank is particularly epic), and it helps that you get to start right where you left off when you die. In fact, even your progress against the boss is saved. This is actually addressed in the story; Horace doesn’t go back in time at these moments, he just has infinite lives and is always able to pick up right where he left off.

The action is broken up by plot elements that further Horace’s understanding of why he exists and how he fits in with those around him. In this regard, the game is continuously intriguing and sweet…if not a bit upsetting at times. But the developers used another trick to change things up; throwback mini-games. At certain points, you’ll find yourself with access to variations of Pac-Man, Space Invaders, Pole Position, and numerous other arcade classics. Horace loves video games, you see. And as you progress, these mini-games become a key part of the experience; they become odd jobs that Horace must perform to raise the money required to get the necessary upgrades.

That’s something I will point out now, as it’s really my only minor quibble with the game. I mentioned earlier that Horace’s mission is to clean a million things. This includes items such as gears, bottles, bikes, and even cars that litter the landscape. You pick them up by standing over them—the bigger the object, the longer you have to stand. Many are out of reach, however, and it’s never clear if you should be able to reach them. After numerous failed attempts on the early levels, I only later found that one of the available upgrades is the ability to have the junk gravitate towards you. So, if you’re a completionist, there’ll be a lot of backtracking to get everything you want. Thankfully the game does tell you if you’ve completely cleaned up an area.

Finally, the overall appearance of the game is wonderful. The retro graphics fit perfectly enhance the techy-tale. Even better, the use of chip-tune classical music adds a decidedly British air of sophistication to the proceedings. Don’t worry, though; although Horace isn’t fond of rock, that doesn’t prevent him from learning the drums.

With its touching story, relatable characters, clever humor, fun gameplay, and appropriate audio/visual aesthetic, Horace has made it to the very top of the platforming options available to Switch gamers. There’s something here for gamers of all types, and it’s accessible by all. Don’t miss it.

Review: Horace (Nintendo Switch)

Awesome

Horace is a pitch-perfect puzzle platformer that expertly balances addictive gameplay with its moving tale of a robot trying to discover himself in a world that makes no sense. It knows why we love video games, and it confirms we’re right to do so.

January 25, 2022

[…] the lovable platformer, is getting a bodily launch by Tremendous Uncommon Video games (try our glowing evaluation right here). With solely 4000 print copies accessible, you’ll have to act quick to get your self a […]

January 25, 2022

[…] the adorable platformer, is getting a physical release by Super Rare Games (check out our glowing review here). With only 4000 print copies available, you’ll need to act fast to get yourself a copy. The […]

February 19, 2022

[…] the adorable platformer, is getting a physical release by Super Rare Games (check out our glowing review here). With only 4000 print copies available, you’ll need to act fast to get yourself a copy. The […]